“I hate Christmas.”

Teachers hear that with surprising regularity around this time of year.

I hate Christmas. I hate Thanksgiving. I hate every holiday.

America’s public school students are living under tremendous pressure.

The social safety net is full of holes. And our children are left to fall through the ripped and torn fabric.

The sad fact is that one in four students in America’s classrooms have experienced a traumatic event.

So if your classroom is typical, 25% of your students have witnessed violence or been subject to a deeply distressing experience.

That could be drug or alcohol abuse, food insecurity, severe beatings, absent caregivers or neglect.

These figures, provided by Neena McConnico, Director of Boston Medical Center’s Child Witness to Violence Project, are indicative of a truth about this country that we don’t want to see.

Our Darwinian public policies leave many children to suffer the effects of poverty – and our society doesn’t want to deal with it.

In impoverished communities, these percentages are even higher and the results more devastating.

The Center for Disease Control’s comprehensive Adverse Childhood Experiences study links the toxic stress of unaddressed trauma to heart disease, liver disease, and mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders.

Young children exposed to more than five adverse experiences in the first three years of life face a 75 percent likelihood of having delays in language, emotional, or brain development, according to McConnico.

This translates directly to negative behaviors in the classroom.

Children who witness violence often have trouble in school because they suffer from post-traumatic stress, which can manifest as inattention, distractibility, hyperactivity, insomnia, aggression, and emotional outbursts.

Or, alternately, these children can sometimes withdraw and appear to be unfazed by their experiences. In some ways, that’s even more dangerous because while they avoid negative attention, they often get no attention at all.

It’s bad enough in the everyday. But it gets worse around the holidays.

Some of it is due to the structure and safety of school being removed. During holiday breaks, children are left to the mercy of sometimes chaotic and uncertain home lives.

Some of it is due to unrealistic expectations inevitably conjured up by the holiday season, itself. Even grown adults have trouble with depression around this time of year. But when you’re a troubled child, the unrealistic expectations and disappointments can be doubly impactful.

Loved ones are missing due to incarceration, divorce, abandonment, health issues, or death. Talk of family gatherings or a special meal can trigger hurt feelings for children who know their caregivers can’t or won’t provide them.

And it’s not always neglect. Sometimes there just isn’t the money for these things. We live in a gig economy where many people work multiple jobs just to survive. All it takes is missing one paycheck or one illness to disrupt holiday celebrations.

Even when parents have enough money, some just don’t bother to buy their kids anything. Sometimes families get to a better financial point but children have had to live through a period of food insecurity and are haunted by it. So even though the household is stable now, kids eat all their treats on the way to school because they always are fearful that the food will run out.

When kids have these sorts of fears, the ubiquitous holiday movies, TV shows, Christmas songs and commercials can set them off further.

It’s the most wonderful time of year for some, but not for all. For many students, the holidays are a time of dread and resentment.

That’s why it’s so important for teachers to be aware of what’s happening to their students.

For the quarter of American children who experience trauma at home, school may be their only safe harbor in a world of storms. Teachers may be the only people they see all day who offer a safe place, a stable environment and a friendly word.

For some kids, teachers are the only adults in their lives who make them feel valuable and supported.

We offer our students so much more than reading, writing and math. We’re allies, mentors, protectors and role models.

I wish we could save them from all the terrors of this world, but we can’t.

Let me be clear – I am in no way a super teacher.

But here are a few things I do in my classroom to help alleviate some of the stresses of the season – and often year round.

1) Prioritize Relationships

Let your kids know you care. The student-teacher relationship is sacred. Nourish it. Be reliable, honest, and dependable.

As Teddy Roosevelt famously said, “Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.”

2) Listen to Them

Sometimes the best thing a teacher can do is just listen to students’ problems. You don’t always have to offer a solution. Our kids are dealing with so many adult pressures. Offering them the ability to get it all out in the presence of a caring adult can be a treasured gift.

“It’s really that simple,” McConnico says. “Listen, reflect back to them that they have been heard, validate the child’s feelings without judgment, and thank the child for sharing with you.”

3) Create Opportunities to be Successful

Some people see teaching as essentially an act of evaluation and assessment. We observe students and then tell them what they did wrong.

This is extremely narrow-minded. When you get to know your students, you can offer them tasks in which you expect they’ll succeed. It’s the kind of thing we do all the time – differentiating instruction and offering choice so that students can achieve the goal in the manner best suited to them.

Sometimes you really have to work at it. If a child has extreme behavior issues, you can observe closely to find the one thing he or she does right and then praise them for it. This doesn’t always work, but when it does, it pays off tremendously!

Positive experiences lead to more positive experiences. It’s like putting training wheels on a bike. It scaffolds learning by supporting kids emotional needs before their academic ones.

4) Routines

I am a huge fan of routine. Kids know exactly what we’re going to do in my class everyday – or at least they have a clear conception of the normal outline of what happens there.

I try to have very clear expectations, timelines and consequences. For kids who live in chaotic homes, this is especially comforting. It’s just another way of creating a safe place where all can learn.

5) There’s Nothing Wrong With Downtime

I know. Teachers are under enormous pressure from administrators to fill every second of the day. But sometimes the best use of class time is giving students a break.

Let students finish assignments in class, read for pleasure, draw, even just daydream and relax. You can overdo it, but everyone can benefit from a little R & R.

This is especially true for traumatized children. Give them time to regroup from the mental and emotional stress. I find that it actually helps motivate kids to work harder when assignments are given.

The holidays can be a stressful time in school.

Kids get overexcited, they can’t concentrate, they’re torn left and right by the various emotions of the season.

As teachers, it’s our job to understand the full scope of what’s going on with our kids and make our classes as nourishing and safe as possible.

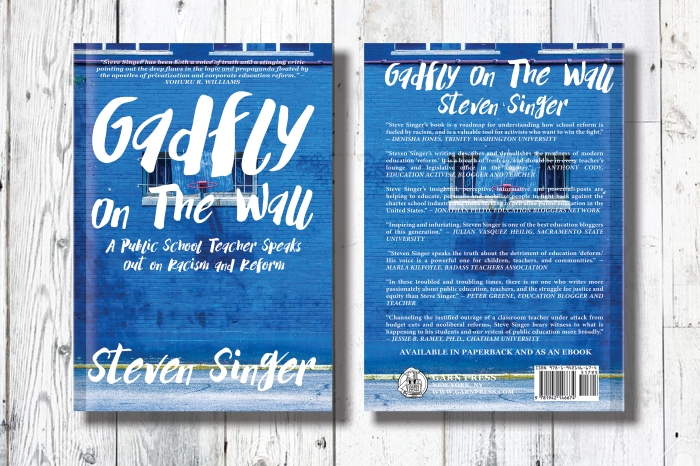

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!