I am a teacher at Steel Valley Schools.

I am also an education blogger.

In order to belong to both worlds, I’ve had to abide by one ironclad rule that I’m about to break:

Never write about my home district.

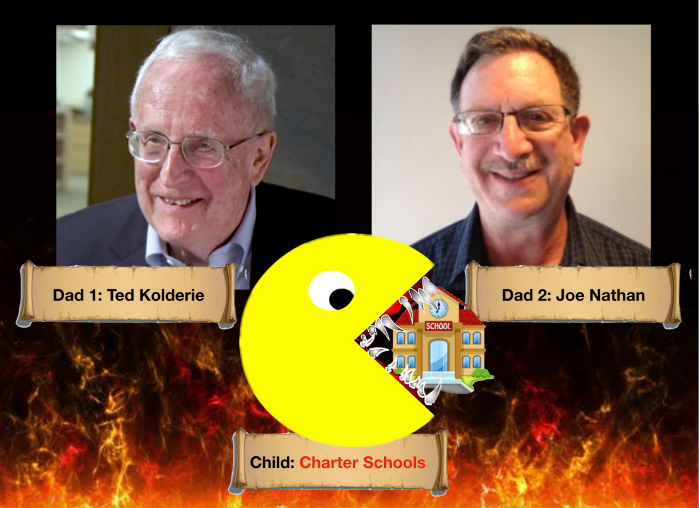

Oh, I write about issues affecting my district. I write about charter schools, standardized testing, child poverty, etc. But I rarely mention how these things directly impact my school, my classroom, or my students.

I change the names to protect the innocent or gloss over the specifics with ambiguity.

In six years, it’s a maxim I’ve disregarded maybe once before – when writing specifically about how charter schools are gobbling up Steel Valley.

Today I’ll set it aside once more – specifically to talk about the insidious school segregation at work in Steel Valley elementary schools.

But let me be clear about one thing – I do this not because I want to needlessly agitate school board members, administrators or community members.

I do it because the district has specifically asked for input from stakeholders – and for the first time in years, teachers (even those living outside district boundaries) have been included in that designation.

School directors held a town hall meeting in October where 246 people crowded into the high school auditorium to present their views.

Last week there was a meeting with teachers and administrators to discuss the same matter.

I didn’t say anything at either gathering though I had many thoughts circling my head.

Instead I have decided to commit them here to my blog.

Maybe no one will read them.

Maybe that would even be best. I know that no matter what invitations are publicly presented, in private what I write could be used against me.

Yet I feel compelled to say it anyway.

So here goes.

Something stinks in Steel Valley School District.

It’s not the smell of excrement or body odor.

It’s a metaphysical stink like crime or poverty.

But it’s neither of those.

It’s school segregation.

To put it bluntly, we have two elementary schools – one mostly for white kids and one mostly for black kids.

Our district is located on a steep hill with Barrett Elementary at the bottom and the other schools – Park Elementary, the middle and high school – at the top.

These schools serve students from K-4th grade. By 5th grade they are integrated once again when they all come to the middle school and then the high school. There the mix is about 40% black to 60% white.

But having each group start their education in distinctly segregated fashion has long lasting effects.

By and large, black students don’t do as well academically as white students. This is due partially to how we assess academic achievement – through flawed and biased standardized tests. But even if we look solely at classroom grades and graduation rates, black kids don’t do as well as the white ones.

Maybe it has something to do with the differences in services we provide at each elementary school. Maybe it has to do with the resources we allocate to each school. Maybe it has something to do with how modern each building is, how new the textbooks, the prevalence of extracurricular activities, tutoring and support each school provides.

But it also has to do with the communities these kids come from and the needs they bring with them to school. It has something to do with the increasing need for special education services especially for children growing up in poverty. It has something to do with the need for structure lacking in home environments, the need for safety, for counseling, for proper nutrition and medical services.

No one group has a monopoly on need. But one group has greater numbers in need and deeper hurts that require healing. And that group is the poor.

According to 2017 Census data, around 27% of our Steel Valley children live in poverty – much more than the Allegheny County average of 17% or the Pennsylvania average of 18%.

And of those poor children, many more are children of color.

Integrating our schools, alone, won’t solve this problem.

Putting children under one roof is an important step, but we have to ensure they get what they need under that roof. Money and resources that flow to white schools can almost as easily be diverted to white classes in the same building. Equity and need must be addressed together.

However, we must recognize that one of those things our children need is each other.

Integration isn’t good just because it raises test scores. It’s good because it teaches our children from an early age what the world really looks like. It teaches them that we’re all human. It teaches tolerance, acceptance and love of all people – and that’s a lesson the white kids need perhaps more than the black kids need help with academics.

I say this from experience.

I grew up in nearby McKeesport – a district very similar to Steel Valley economically, racially and culturally.

I am the product of integrated schools and have benefited greatly from that experience. My daughter goes to McKeesport and likewise benefits from growing up in that inclusive environment.

I could have enrolled her elsewhere. But I didn’t because I value integration.

So when Mary Niederberger wrote her bombshell article in Public Source about the segregated Steel Valley elementary schools, I was embarrassed like everyone else.

But I wasn’t shocked.

To be frank, none of us were shocked.

We all knew about the segregation problem at the elementaries. Anyone who had been to them and can see knew about it.

In fact, to the district’s credit, Steel Valley had already tried a partial remedy. The elementaries used to house K-5th grade. We moved the 5th grade students from each elementary up to the middle school thereby at least reducing the years in which our students were segregated.

The result was state penalty.

Moving Barrett kids who got low test scores up to the middle school – which had some of the best test scores in the district – tipped the scales. The state penalized both Barrett and the middle school for low test scores and required that students in each school be allowed to take their per pupil funding as a tax voucher and use it toward tuition at a private or parochial school – as if there was any evidence doing so would help them academically.

Not exactly an encouragement to increase the program.

But school segregation has a certain smell that’s hard to ignore.

If you’ll allow me a brief diversion, it reminds me of a historical analogue of which you’ve probably never heard – the Great Stink of 1858.

Let me take you back to London, England, in Victorian times.

The British had been using the Thames River to wash away their garbage and sewage for centuries, but the river being a tidal body wasn’t able to keep up with the mess.

Moreover, getting your drinking water from the same place you use to wash away your sewage isn’t exactly a healthy way to live.

But people ignored it and went on with their lives as they always did (if they didn’t die of periodic cholera outbreaks) until 1858.

That year was a particularly dry and hot one and the Thames nearly evaporated into a dung-colored slime.

It stunk.

People from miles away could smell it.

There’s a funny story of Queen Victoria traveling by barge down the river with a bouquet of flowers shoved in her face so she could breathe. Charles Dickens and others made humorous remarks.

But the politicians of the time refused to do anything to fix the problem. They sprayed lime on the curtains. They even sprayed it onto the fecal water – all to no avail.

Finally, when they had exhausted every other option, they did what needed to be done. They spent 4.2 million pounds to build a more than 1,000 mile modern sewage system under London.

It took two decades but they did it right and almost immediately the cholera outbreaks stopped.

They calculated how big a sewage system would have to be constructed for the contemporary population and then made it twice as big. And the result is still working today!

Scientists estimate if they hadn’t doubled the size it would have given out by the 1950s.

This seems to be an especially important bit of history – even for Americans more than a continent and a century distant.

It seems to me an apt metaphor for what we’re experiencing here in Steel Valley.

Everyone knows what’s causing the stink in our district – school segregation.

Likewise, we know what needs to be done to fix it.

We need a new elementary complex for all students K-4. (I’d actually like to see 5th grade there, too.) And we need busing to get these kids to school regardless of where they live.

The excuse for having two segregated elementary schools has typically been our segregated communities and lack of adequate public transportation.

We’re just a school district. We can’t fix the complex web of economic, social and racial issues behind where people live (though these are matters our local, state and federal governments can and should address). However, we can take steps to minimize their impact at least so far as education is concerned.

But this requires busing – something leaders decades ago decided against in favor of additional funding in the classroom.

In short, our kids have always walked to school. Kids at the bottom of the hill in Homestead and West Homestead walk to Barrett. Kids at the top in Munhall walk to Park. But we never required elementary kids to traverse that hill up to the middle and high school until they were at least 10 years old.

We didn’t think it fair to ask young kids to walk all the way up the hill. Neighborhood schools reduced the distance – but kept the races mostly separate.

We need busing to remove this excuse.

I’ve heard many people deny both propositions. They say we can jury rig a solution where certain grades go to certain schools that already exist just not on a segregated basis. Maybe K-2 could go to Park and 3-4 could go to Barrett.

It wouldn’t work. The existent buildings will not accommodate all the children we have. Frankly, the facilities at Barrett just aren’t up to standard. Even Park has seen better days.

We could renovate and build new wings onto existing schools, but it just makes more sense to build a new school.

After all, we want a solution that will last for years to come. We don’t want a Band-Aid that only lasts for a few years.

Some complain that this is impossible – that there just isn’t enough money to get this done.

And I do sympathize with this position. After all, as Superintendent Ed Wehrer said, the district is still paying off construction of the high school, which was built in the 1970s.

But solutions do exist – even for financial problems.

My home district of McKeesport is very similar to Steel Valley and in the last decade has built a new 6th grade wing to Founders Hall Middle School and Twin Rivers, a new K-4 school on the old Cornell site.

I’m sure McKeesport administrators and school board members along with those at other neighboring districts could provide Steel Valley with the expertise we need to get this done. I’m sure we could find the political will to help us get this done.

And that’s really my point: our problem is less about what needs to happen than how to do it.

We should at least try to do this right!

We can’t just give up before we’ve even begun.

Debates can and should be had about where to build the new school, how extensive to have the busing and other details. But the main plan is obvious.

I truly believe this is doable.

I believe we can integrate Steel Valley elementary schools. And I believe we can – and MUST – do so without any staff furloughs.

We’re already running our classes with a skeleton crew. We can ensure the help and participation of teachers by making them this promise.

That’s what true leaders would do.

Sure, some fools will complain about sending their little white kids to class with black kids. We heard similar comments at the town hall meeting. But – frankly – who cares what people like that think? The best thing we could do for their children would be to integrate the schools so that parental prejudices come smack into conflict with the realities of life.

And if doing so makes them pull out of Steel Valley, good riddance. You never need to justify doing the right thing.

Again this will not solve all of our problems. We will still need to work to meet all student needs in their buildings. We will have to continue to fight the charter school parasites sucking at our district tax revenues.

But this is the right thing to do.

It is the only way to clear the air and remove the stink of decades of segregation.

So let’s do it.

Let’s join together and get it done.

Who’s with me?

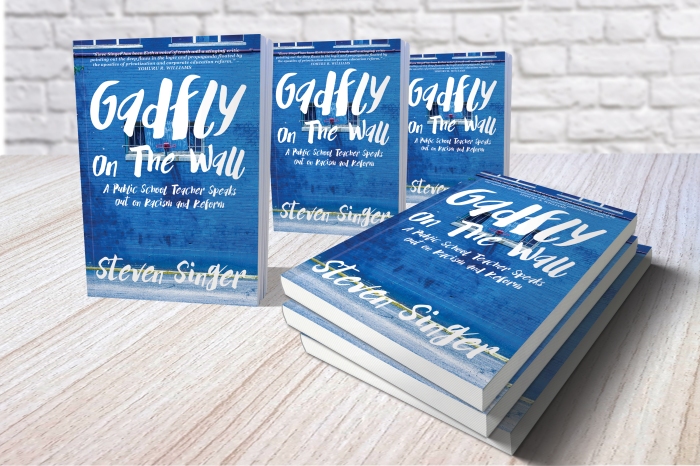

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!