For most of my life, the United States has been neglecting its public school children – especially the black and brown ones.

Since the mid 1970s, instead of integrating our schools, we’ve been slowly resegregating them on the basis of race and social class.

Since the 1980s, instead of measuring academic success by the satisfaction of an individuals curiosity and authentic learning, we’ve been slowly redefining it to mean nothing but achievement on standardized tests.

And since the 1990s, instead of making sure our schools meet the needs of all students, we’ve been slowly allowing charter schools to infect our system of authentic public education so that business interests are education’s organizing principle.

But now, for the first time in at least 60 years, a mainstream political candidate running for President has had the courage to go another way.

And that person is Bernie Sanders.

We didn’t see this with Barack Obama. We didn’t see it with Bill Clinton. We certainly didn’t see it with any Republican Presidents from Reagan to the Bushes to Trump.

Only Sanders in his 2020 campaign. Even among his Democratic rivals for the party’s nomination – Warren, Biden, Harris, Booker and a host of others – he stands apart and unique. Heck! He’s even more progressive today on this issue than he was when he ran in 2015.

It doesn’t take a deep dive into the mass media to find this out. You don’t have to parse disparate comments he made at this rally or in that interview. If you want to know what Bernie thinks about education policy, you can just go on his campaign Website and read all about it.

The other candidates barely address these issues at all. They may be open about one or even two of them, but to understand where they stand on education in total – especially K-12 schooling – you have to read the tea leaves of who they’ve selected as an education advisor or what they wrote in decades old books or what offhand comments they made in interviews.

In almost every regard, only Sanders has the guts to tell you straight out exactly what he thinks. And that’s clear right from the name of his proposal.

He calls it “A Thurgood Marshall Plan for Public Education.”

Why name his agenda after the first black Supreme Court justice? Because prior to accepting a nomination to the highest court in the land, Marshall argued several cases before that court including the landmark Brown v. Board of Education. He also founded the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. Not only did Marshall successfully argue that school segregation violated the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution, but he spent his life fighting for civil rights.

Sanders is the only candidate out there today brave enough to connect those dots. The fight against segregation, high stakes testing and school privatization is a fight for civil rights.

That is clear in nearly every aspect of his plan.

I’m not saying it’s perfect. He doesn’t go as far as he might in some areas – especially against high stakes testing. But his plan is so far advanced of anything anyone else has even considered, it deserves recognition and strong consideration.

So without further ado, I give you the top 10 reasons Bernie Sanders’ education platform is the most progressive in modern American history:

1) He Proposes Fighting School Segregation and Racial Discrimination

Sanders understands that many of our public schools today are more segregated than they were 65 years ago when Brown v. Board was decided. Only 20 percent of our teachers are nonwhite – even in schools that serve a majority of black and brown children. Implicit racial bias puts these students at risk of higher suspensions, unfair discipline policies and an early introduction into the criminal justice system through the school-to-prison pipeline.

Bernie proposes we increase funding to integrate schools, enforce desegregation orders and appoint federal judges who will support these measures. He wants to triple Title I funding for schools serving poor and minority children and increase funding for English as a Second Language programs. He even suggests racial sensitivity training for teachers and better review of civil rights complaints and discipline policies.

This could have an amazingly positive impact on our schools. Imagine a school system where people of all different races, nationalities, sexualities and creeds could meet and get to know one another. It’s harder to be racist and prejudiced adults when as children you learned not to consider people different than you as an other. It’s also harder to withhold funding and opportunities to minority populations when you mix all children together in the same schools.

2) He Would Ban For-Profit Charter Schools

This is a case of Bernie just listening to what educators, school directors and civil rights organizations like the NAACP are already saying. Charter schools are publicly funded but privately operated. Though this differs somewhat from state to state, in general it means that charters don’t have to abide by the same rules as the authentic public schools in the same neighborhoods. They can run without an elected school board, have selective enrollment, don’t have to provide the same services for students especially those requiring special education, and they can even cut services for children and pocket the savings as profit.

Moreover, charters increase segregation – 17 percent of charter schools are 99 percent minority, compared to 4 percent of traditional public schools.

To reverse this trend, Bernie would ban for-profit charter schools and impose a moratorium on federal dollars for charter expansion until a national audit was conducted. That means no more federal funds for new charter schools.

Moving forward, charter schools would have to be more accountable for their actions. They would have to comply with the same rules as authentic public schools, open their records about what happens at these schools, have the same employment practices as at the neighborhood authentic public school, and abide by local union contracts.

I know. I know. I might have gone a bit further regulating charter schools, myself, especially since the real difference between a for-profit charter school and a non-profit one is often just its tax status. But let’s pause a moment here to consider what he’s actually proposing.

If all charter schools had to actually abide by all these rules, they would almost be the same as authentic public schools. This is almost tantamount to eliminating charter schools unless they can meet the same standards as authentic public schools.

I think we would find very few that could meet this standard – but those that did could – with financial help – be integrated into the community school system as a productive part of it and not – as too many are now – as parasites.

Could Bernie as President actually do all of this? Probably not considering that much of charter school law is controlled by the states. But holding the bully pulpit and (with the help of an ascendant Democratic legislature?) the federal purse strings, he could have a transformative impact on the industry. It would at least change the narrative and the direction these policies have been going. It would provide activists the impetus to make real change in their state legislatures supporting local politicians who likewise back the President’s agenda.

3) He’d Push for Equitable School Funding

Bernie understands that our public school funding system is a mess. Most schools rely on local property taxes to make up the majority of their funding. State legislatures and the federal government shoulder very little of the financial burden. As a result, schools in rich neighborhoods are well-funded and schools in poor neighborhoods go wanting. This means more opportunities for the already privileged and less for the needy.

Bernie proposes rethinking this ubiquitous connection between property taxes and education, establishing a nationwide minimum that must be allocated for every student, funding initiatives to decrease class size, and supporting the arts, foreign language acquisition and music education.

Once again, this isn’t something the President can do alone. He needs the support of Congress and state legislatures. But he could have tremendous influence from the Oval Office and even putting this issue on the map would be powerful. We can’t solve problems we don’t talk about – and no one else is really talking much about this. Imagine if the President was talking about it every day on the news.

4) He’d Provide More Funding for Special Education Students

Students with special needs cost more to educate than those without them. More than four decades ago, the federal government made a promise to school districts around the country to fund 40 percent of the cost of special education. It’s never happened. This chronic lack of funding translates to a shortage of special education teachers and physical and speech therapists. Moreover, the turnover rate for these specialists is incredibly high.

Bernie wants to not only fulfill the age old promise of special education funding but to go beyond it. He proposes the federal government meet half the cost for each special needs student. That, alone, would go a long way to providing financial help to districts and ensuring these children get the extra help they need.

5) He Wants to Give Teachers a Raise

Teachers are flooding out of the classroom because they often can’t survive on the salaries they’re being paid. Moreover, considering the amount of responsibilities heaped on their shoulders, such undervaluing is not only economically untenable, it is psychologically demoralizing and morally unfair. As a result, 20 percent of teachers leave the profession within five years – 40 percent more than the historical average.

Bernie suggests working with states to ensure a minimum starting salary of $60,000 tied to cost of living, years of service, etc. He also wants to protect and expand collective bargaining and tenure, allow teachers to write off at least $500 of expenses for supplies they buy for their classrooms, and end gender and racial discrepancies in teacher salaries.

It’s an ambitious project. I criticized Kamala Harris for proposing a more modest teacher pay raise because it wasn’t connected to a broad progressive education platform like Sanders. In short, we’ve heard neoliberal candidates make good suggestions in the past that quickly morphed into faustian bargains like merit pay programs – an initiative that would be entirely out of place among Sanders initiatives.

In Harris’ case, the devil is in the details. In Sanders, it’s a matter of the totality of the proposal.

6) He Wants to Expand Summer School and After School Programs

It’s no secret that while on summer break students forget some of what they’ve learned during the year and that summer programs can help reduce this learning loss. Moreover, after school programs provide a similar function throughout the year and help kids not just academically but socially. Children with a safe place to go before parents get home from work avoid risky behaviors and the temptations of the streets. Plus they tend to have better school attendance, better relationships with peers, better social and emotional skills, etc.

Under the guidance of Betsy Devos, the Trump administration has proposed cutting such programs by $2 billion. Bernie is suggesting to increase them by $5 billion. It’s as simple as that. Sanders wants to more than double our current investment in summer and after school programs. It’s emblematic of humane and rational treatment of children.

7) He Wants to Provide Free Meals for All Students Year-Round

One in six children go hungry in America today. Instead of shaming them with lunch debts and wondering why they have difficulty learning on an empty stomach, Bernie wants to feed them free breakfast, lunch and even snacks. In addition, he doesn’t want to shame them by having the needy be the only ones eligible for these free meals. This program would be open to every child, regardless of parental wealth.

It’s an initiative that already exists at many Title I schools like the one where I teach and the one where my daughter goes to school. I can say from experience that it is incredibly successful. This goes in the opposite direction of boot strapped conservatives like Paul Ryan who suggested a free meal gives kids an empty soul. Instead, it creates a community of children who know that their society cares about them and will ensure they don’t go hungry.

That may seem like a small thing to some, but to a hungry child it can make all the difference.

8) He Wants to Transform all Schools into Community Schools

This is a beautiful model of exactly what public education should be.

Schools shouldn’t be businesses run to make a profit for investors. They should be the beating heart of the communities they serve. Bernie thinks all schools should be made in this image and provide medical care, dental services, mental health resources, and substance abuse prevention. They should furnish programs for adults as well as students including job training, continuing education, art spaces, English language classes and places to get your GED.

Many schools already do this. Instead of eliminating funding for these types of schools as the Trump administration has suggested, Bernie proposes providing an additional $5 billion in annual funding for them.

9) He Would Fix Crumbling Schools

America’s schools, just like her roads and bridges, are falling into disrepair. A 2014 study found that at least 53 percent of the nation’s schools need immediate repair. At least 2.3 million students, mostly in rural communities, attend schools without high-speed internet access. Heating and cooling systems don’t work.

Some schools have leaks in their roofs. This is just not acceptable.

Bernie wants to fix these infrastructure issues while modernizing and making our schools green and welcoming.

10) He Wants to Ensure All Students are Safe and Included

Our LGBTQ students are at increased risk of bullying, self harm and suicide. We need schools where everyone can be safe and accepted for who they are.

Bernie wants to pass legislation that would explicitly protect the rights of LGBTQ students and protect them from harassment, discrimination and violence. He is also calling for protection of immigrant students to ensure that they are not put under surveillance or harassed due to their immigration status. Finally, this project includes gun violence prevention to make school shootings increasingly unlikely.

There are a lot of issues that fall under this umbrella, but they are each essential to a 21st Century school. Solutions here are not easy, but it is telling that the Sanders campaign includes them as part of his platform.

So there you have it – a truly progressive series of policy proposals for our schools.

Not since Lyndon Johnson envisioned the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) has there been a more far reaching and progressive set of education initiatives.

What About High Stakes Testing?

Unfortunately, that also highlights Sanders biggest weakness.

Johnson’s signature legislation which had been focused on addressing funding disparities in 1965 became under George W. Bush in the 2000s a way of punishing poor schools for low standardized test scores.

The glaring omission from Sanders plan is anything substantive to do with high stakes testing.

The Thurgood Marshall plan hardly mentions it at all. In fact, the only place you’ll find testing is in the introduction to illustrate how far American education has fallen behind other countries and in this somewhat vague condemnation:

“We must put an end to high-stakes testing and “teaching to the test” so that our students have a more fulfilling educational life and our teachers are afforded professional respect.”

However, it’s troubling that for once Bernie doesn’t tie a political position with a specific policy. If he wants to “end high-stakes testing,” what exactly is his plan to do so? Where does it fit within his education platform? And why wasn’t it a specific part of the overall plan?

Thankfully, it is addressed in more detail on FeelTheBern.org – a Website not officially affiliated with Sanders but created by volunteers to spread his policy positions.

After giving a fairly good explanation of the problems with high stakes testing, it references this quote from Sanders:

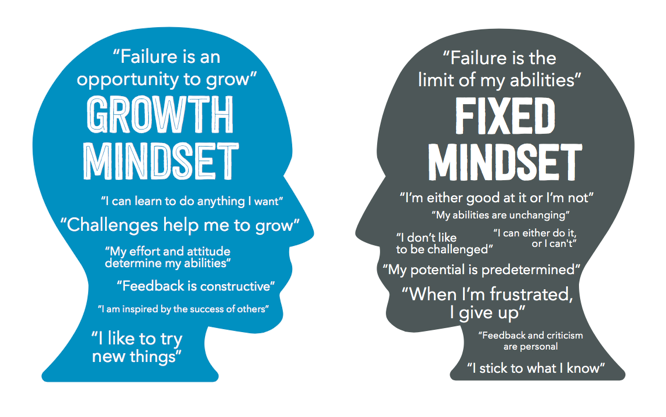

“I voted against No Child Left Behind in 2001, and continue to oppose the bill’s reliance on high-stakes standardized testing to direct draconian interventions. In my view, No Child Left Behind ignores several important factors in a student’s academic performance, specifically the impact of poverty, access to adequate health care, mental health, nutrition, and a wide variety of supports that children in poverty should have access to. By placing so much emphasis on standardized testing, No Child Left Behind ignores many of the skills and qualities that are vitally important in our 21st century economy, like problem solving, critical thinking, and teamwork, in favor of test preparation that provides no benefit to students after they leave school.”

The site suggests that Bernie supports more flexibility in how we determine academic success. It references Sanders 2015 vote for the Every Child Achieves Act which allows for states to create their own accountability systems to assess student performance.

However, the full impact of this bill has not been as far reaching as advocates claimed it would be. In retrospect, it seems to represent a missed opportunity to curtail high stakes testing more than a workaround of its faults.

In addition, the site notes the problems with Common Core and while citing Sanders reticence with certain aspects of the project admits that he voted in early 2015 against an anti-Common Core amendment thereby indicating opposition to its repeal.

I’ll admit this is disappointing. And perplexing in light of the rest of his education platform.

It’s like watching a vegan buy all of his veggies at Whole Foods and then start crunching on a slice of bacon, or like a gay rights activist who takes a lunch break at Chick-fil-a.

My guess is that Sanders hasn’t quite got up to speed on the issue of standardized testing yet. However, I can’t imagine him supporting it because, frankly, it doesn’t fit in with his platform at all.

One wonders what the purpose of high stakes testing could possibly be in a world where all of his other education goals were fulfilled.

If it were up to me, I’d scrap high stakes testing as a waste of education spending that did next to nothing to show how students or schools were doing. Real accountability would come from looking at the resources actually provided to schools and what schools did with them. It would result from observing teachers and principals to see what education they actually provided – not some second hand guessing game based on the whims of corporations making money on the tests, the grading of the tests and the subsequent remediation materials when students failed.

For me, the omission of high stakes testing from Sanders platform is acceptable only because of the degree of detail he has already provided in nearly every other aspect. There are few areas of uncertainty here. Unlike any other candidate, we know pretty well where Sanders is going.

It is way more likely that advocates could get Sanders to take a more progressive and substantial policy stand on this issue than that he would suddenly become a standardized testing champion while opposing everything else in the school privatization handbook.

Conclusion

So there it is.

Bernie Sanders has put forth the most progressive education plan in more than half a century.

It’s not perfect, but it’s orders of magnitude better than the plans of even his closest rival.

This isn’t to say that other candidates might not improve their education projects before the primary election. I hope that happens. Sanders has a knack for moving the conversation further left.

However, he is so far ahead, I seriously doubt that anyone else will be able to catch him here.

Who knows what the future will bring, but education advocates have a clear first choice in this race – Bernie Sanders.

He is the only one offering us a real future we can believe in.

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!