I work very hard on this blog.

It’s not exactly easy to fit in so many articles – 53 so far this year – between teaching full time.

And I’ve been doing it for 8 years – since July 2014.

In that time, this site has earned 2.3 million hits – 218,603 just this year.

I’m proud of the work I’ve done here.

I haven’t changed the world, but I’ve been heard. Occasionally.

As a classroom teacher, that’s really what I’m trying to do. In my everyday work, few people whose grade I’m not calculating actually listen to me. And even then it’s not always a given.

I want to believe my words have an impact – that policymakers read what I write and consider it before offering new measures and revising old ones.

But as time goes on, I wonder if any of that actually happens. These days my writing feels more like a shout in the dark than anything else.

At best, from the comments I often get on my articles (and the fact that 14,887 people have signed up to follow my work), it seems at least that I am not shouting alone.

We are all yearning to be heard.

These are the cries that most of us seemed to have in common this year:

10) Top 6 Administrative Failures of the Pandemic Classroom

Published: May 22

Views: 3,014

Description: This is a postmortem on the 2020-21 school year. Here are the six policies that really weren’t working from social distancing, to cyber school, hybrid models, and more.

Fun Fact: I had hoped that laying out last year’s failures might stop them from being tried again this year or at least we might revise them into policies that worked. In some instances – like cyber school – there seems to have been an attempt to accomplish this. In others – like standardized testing – we just can’t seem to stop ourselves from repeating the same old mistakes.

9) Why Does Your Right to Unmask Usurp My Child’s Right to a Safe School?

Published: Aug 17

Views: 3,151

Description: It seemed like a pretty easy concept when I first learned it back in civics class. Your right to freedom ends when it comes into conflict with mine. But in 2021, that’s all out the window. Certain people’s rights to comfort (i.e. being unmasked) are more important than other people’s right to life (i.e. being free from your potential Covid).

Fun Fact: This was republished in CommonDreams.org and discussed on Diane Ravitch’s blog.

8) Stop Normalizing the Exploitation of Teachers

Published: Nov. 26

Views: 3,716

Description: Demands on teachers are out of control – everything from new scattershot initiatives to more paperwork to having to forgo our planning periods and sub for missing staff nearly every day. And the worse part is that each time it’s done, it becomes the new normal. Teaching should not be death by a million cuts.

Fun Fact: This was another in what seemed to be a series of articles about how teaching has gotten more intolerable this year. If anyone ever wonders what happened to all the teachers once we all leave, refer to this series.

7) Top Five Actions to Stop the Teacher Exodus During COVID and Beyond

Published: Oct. 7

Views: 5,112

Description: Teachers are leaving the profession at an unprecedented rate this year. So what do we do about it? Here are five simple things any district can do that don’t require a lot of money or political will. They just require wanting to fix the problem. These are things like eliminating unnecessary tasks and forgoing formal lesson plans while increasing planning time.

Fun Fact: Few districts seems to be doing any of this. It shows that they really don’t care.

6) I Love Teaching, But…

Published: Dec. 20

Views: 5,380

Description: This is almost a poem. It’s just a description of many of the things I love about teaching and many of the things I don’t. It’s an attempt to show how the negatives are overwhelming the positives.

Fun Fact: This started as a Facebook post: “I love teaching. I don’t love the exhaustion, the lack of planning & grading time, the impossibly high expectations & low pay, the lack of autonomy, the gaslighting, the disrespect, being used as a political football and the death threats.”

5) My Students Haven’t Lost Learning. They’ve Lost Social and Emotional Development

Published: Sept. 30

Views: 6,422

Description: Policymakers and pundits keep saying students are suffering learning loss from last year and the interrupted and online classes required during the pandemic. It’s total nonsense. Students are suffering from a lack of social skills. They don’t know how to interact with each other and how to emotionally process what’s been going on.

Fun Fact: This idea is so obvious to anyone who’s actually in school buildings that it has gotten through somewhat to the mass media. However, the drum of bogus learning loss is still being beaten by powerful companies determined to make money off of this catastrophe.

4) You’re Going to Miss Us When We’re Gone – What School May Look Like Once All the Teachers Quit

Published: Feb. 20

Views: 9,385

Description: Imagine a world without teachers. You don’t have to. I’ve done it for you. This is a fictional story of two kids, DeShaun and Marco, and what their educational experience may well be like once we’ve chased away all the education professionals.

Fun Fact: This is one of my own favorite pieces of the year, and it is based on what the ed tech companies have already proposed.

3) The Teacher Trauma of Repeatedly Justifying Your Right To Life During Covid

Published: Jan 16

Views: 9,794

Description: How many times have teachers had to go to their administrators and school directors asking for policies that will keep them and their students safe? How many times have we been turned down? How many times can we keep repeating this cycle? It’s like something out of Kafka or Gogol.

Fun Fact: It may not be over.

2) Teachers Are Not Okay

Published: Sept. 23

Views: 14,592

Description: This was my first attempt to discuss how much worse 2021-2022 is starting than the previous school year. Teachers are struggling with doing their jobs and staying healthy. And no one seems to care.

Fun Fact: My own health was extremely poor when I wrote this. I was in and out of the hospital. Though I feel somewhat better now, not much has changed. This article was republished in the Washington Post, on CommonDreams.org, and discussed on Diane Ravitch’s blog.

1) Teachers Absorb Student Trauma But Don’t Know How to Get Rid of the Pain

Published: Nov. 10

Views: 40,853

Description: Being there for students who are traumatized by the pandemic makes teachers subject to vicarious trauma, ourselves. We are subject to verbal and physical abuse in the classroom. It is one of the major factors wearing us down, and there appears to be no help in site – nor does anyone even seem to acknowledge what is happening.

Fun Fact: This one really seemed to strike a nerve with my fellow teachers. I heard so many similar stories from educators across the country who are going through these same things.

Like this post? You might want to consider becoming a Patreon subscriber. This helps me continue to keep the blog going and get on with this difficult and challenging work.

Plus you get subscriber only extras!

Just CLICK HERE.

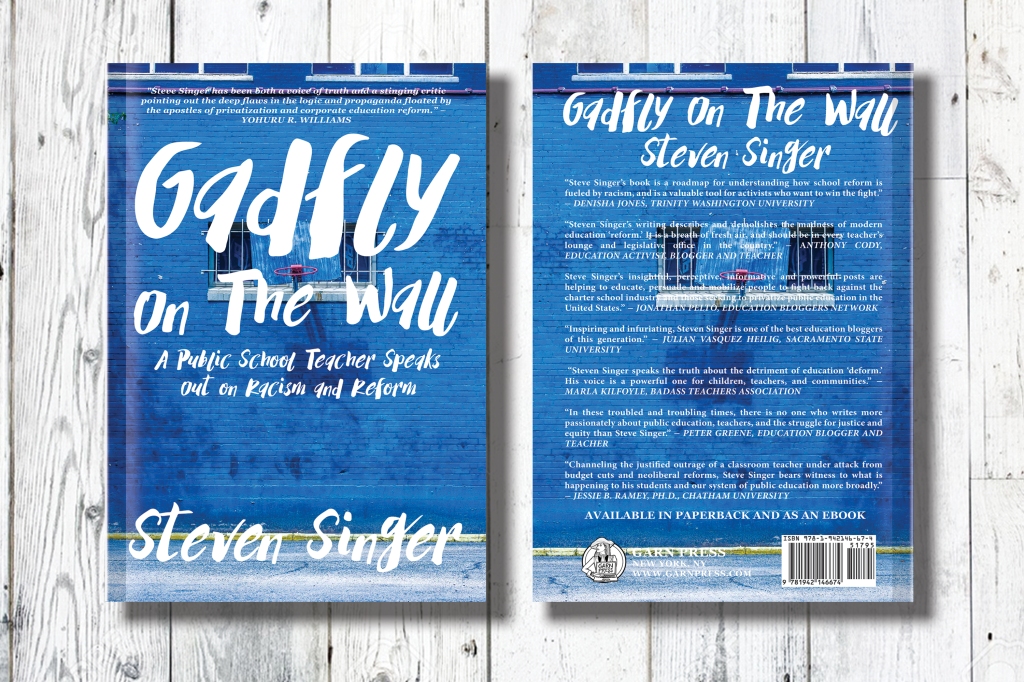

I’ve also written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!