I hate to be blunt here, but economists need to shut the heck up.

Never has there been a group more concerned about the value of everything that was more incapable of determining anything’s true worth.

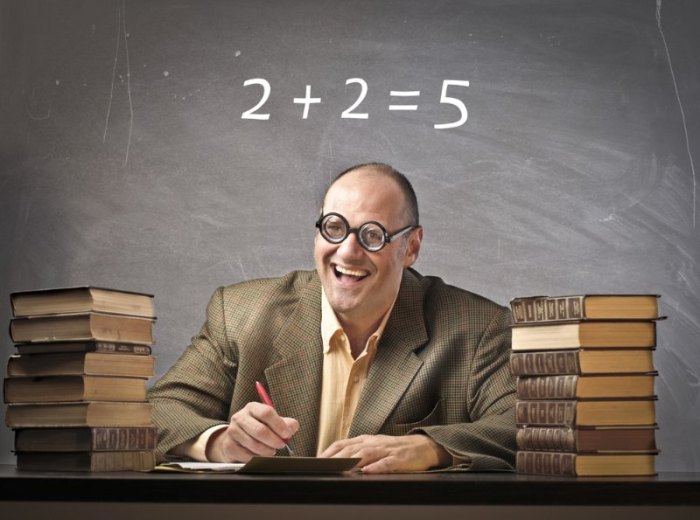

They boil everything down to numbers and data and never realize that the essence has evaporated away.

I’m sorry but every human interaction isn’t reducible to a monetary transaction. Every relationship isn’t an equation.

Some things are just intrinsically valuable. And that’s not some mystical statement of faith – it’s just what it means to be human.

Take education.

Economists love to pontificate on every aspect of the student experience – what’s most effective – what kinds of schools, which methods of assessment, teaching, curriculum, technology, etc. Seen through that lens, every tiny aspect of schooling becomes a cost analysis.

And, stupid us, we listen to them as if they had some monopoly on truth.

But what do you expect from a society that worships wealth? Just as money is our god, the economists are our clergy.

How else can you explain something as monumentally stupid as Bryan Caplan’s article published in the LA Times “What Students Know That Experts Don’t: School is All About Signaling, Not Skill-Building”?

In it, Caplan, a professor of economics at George Mason University, theorizes why schooling is pointless and thus education spending is a waste of money.

It would be far better in Caplan’s view to use that money to buy things like… oh… his new book “The Case Against Education: Why the Education System Is a Waste of Time and Money.”

His argument goes something like this: the only value of an education is getting a job after graduation.

Businesses only care about school because they think it signifies whether prospective employees will be good or bad at their jobs. And students don’t care about learning – they only care about appearing to have learned something to lure prospective employers. Once you’re hired, if you don’t have the skills, employers have an incentive to give you on the job training. Getting an education is just about getting a foot in the door. It’s all just a charade.

Therefore, we should cut education funding and put kids to work in high school where they can learn how to do the jobs they’ll need to survive.

No wonder economics is sometimes called “The Dismal Science.” Can you imagine having such a dim view of the world where THAT load of crap makes sense?

We’re all just worker drones and education is the human equivalent of a mating dance or brilliant plumage – but instead of attracting the opposite sex, we’re attracting a new boss.

Bleh! I think I just threw up in my mouth a little bit.

This is what comes of listening to economists on a subject they know nothing about.

I’m a public school teacher. I am engaged in the act of learning on a daily basis. And let me tell you something – it’s not about merely signifying.

I teach 7th and 8th grade language arts. My students aren’t simply working to appear literate. They’re actually attempting to express themselves in words and language. Likewise, my students aren’t just working to appear as if they can comprehend written language. They’re actually trying to read and understand what the author is saying.

But that’s only the half of it.

Education isn’t even just the accumulation of skills. Students aren’t hard drives and we’re not simply downloading information and subroutines into their impressionable brains.

Students are engaged in the activity of becoming themselves.

Education isn’t a transaction – it’s a transformation.

When my students read “The Diary of Anne Frank” or To Kill a Mockingbird, for example, they become fundamentally different people. They gain deep understandings about what it means to be human, celebrating social differences and respecting human dignity.

When my students write poetry, short fiction and essays, they aren’t merely communicating. They’re compelled to think, to have an informed opinion, to become conscious citizens and fellow people.

They get grades – sure – but what we’re doing is about so much more than A-E, advanced, proficient, basic or below basic.

When the year is over, they KNOW they can read and understand complex novels, plays, essays and poems. The maelstrom of emotions swirling round in their heads has an outlet, can be shared, examined and changed.

Caplan is selling all of that short because he sees no value in it. He argues from the lowest common denominator – no, he argues from the lowest actions of the lowest common denominator to extrapolate a world where everything is neatly quantifiable.

It’s not hard to imagine why an economist would be seduced by such a vision. He’s turned the multi-color world into black and white hues that best suit his profession.

In a way, I can’t blame him for that. For a carpenter, I’m sure most problems look like a hammer and a nail. For a surgeon, everything looks like a scalpel and sutures.

But shame on us for letting one field’s myopia dominate the conversation.

No one seems all that interested in my economic theories about how to maximize gross domestic product. And why would they? I’m not an economist.

However, it’s just as absurd to privilege the ramblings of economists on education. They are just as ignorant – perhaps more so.

It is a symptom of our sick society.

We turn everything into numbers and pretend they can capture the reality around us.

This works great for measuring angles or determining the speed of a rocket. But it is laughably unequipped to measure interior states and statements of real human value.

That’s why standardized tests are inadequate.

It’s why value added teacher evaluations are absurd. It’s why Common Core is poppycock.

Use the right tool for the right job.

If you want to measure production and consumption or the transfer of wealth, call an economist.

If you want to understand education, call a teacher.