“We need to change accountability for schools to be more holistic. My greatest frustration is that I can’t do it fast enough.”

–Pedro Rivera, Pennsylvania’s Education Secretary

Parents, you can.

It doesn’t matter where you live. It doesn’t matter what laws are on the books. It doesn’t matter if your state is controlled by Democrats, Republicans or some combination thereof.

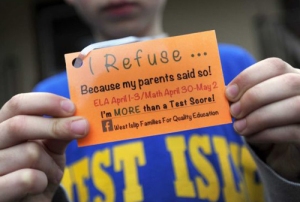

No government – not federal, state or local – can trample your parental rights. If you don’t want your child to be evaluated based on standardized tests, your child doesn’t have to be. And if a majority of parents nationwide make this decision, the era of standardized testing comes to an end. Period.

It has already begun.

Across the nation last school year, parents decided to opt their children out of standardized testing in historic numbers. The government noticed and functionaries from New York to California and all places in between are scrambling to deal with it.

In the Empire State one in five students didn’t take federally mandated standardized tests. State education commissioner Mary Ellen Elia responded yesterday by threatening sanctions against schools this year with high opt out numbers. In short, if in the coming year too many kids don’t take the test in a given school, the state will withhold funding.

It’s a desperate move. If the public doesn’t like what its duly elected officials and their functionaries are doing, those same officials and functionaries are vowing to punish the public. But wait. Don’t those people work for the public? Isn’t it their job to do our will? It’s not our job to do theirs.

The message was received a bit better in U.S. Congress where the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) is being reauthorized. Two drafts of the law that governs K-12 public schools were approved – one in the House and one in the Senate. And both specifically allow parents to opt their children out of standardized testing. But can schools be punished for it?

The House version says no. The Senate version says it’s up to each state legislature.

These bills are being combined before being presented to President Obama for his signature. If he doesn’t veto the result, one might assume that at worst the issue will become each state’s prerogative.

But you’d be wrong. The state has as much business deciding this matter as does the fed – which is none. This is a parental rights issue. No one has the right to blackmail parents to fall in line with any government education policy. It’s the other way around.

In my own state of Pennsylvania, opt out numbers this year were not as dramatic as in New York, but they still sent a message to state government.

The number of students opted out of state tests tripled in 2015, according to data from the Pennsylvania Department of Education. PSSA math opt-outs rose to 3,270 students from 1,064 in 2014. PSSA English language arts opt-outs rose to 3,245 from 1,068. Those are the largest jumps in the nine years of available data.

And it’s not only parents who are concerned. Teachers continue to speak out against high stakes standardized tests.

Thousands of teachers have told State Education Secretary Pedro Rivera that school accountability needs to be less about test scores and more about reading levels, attendance, school climate, and other measures, he said. They have concerns about graduation requirements and the state’s current system of evaluating schools.

It’s not like these criticism are new. Education experts have been voicing them since at least 1906 when the New York State Department of Education advised the legislature as follows:

“It is a very great and more serious evil to sacrifice systematic instruction and a comprehensive view of the subject for the scrappy and unrelated knowledge gained by students who are persistently drilled in the mere answering of questions issued by the Education Department or other governing bodies.”

-Sharon L. Nichols and David Berliner, Collateral Damage: How High Stakes Testing Corrupts America’s Schools, 2007

Corporate education reformers complain that testing is necessary to hold schools accountable. However, the results are not trustworthy, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Education, itself! In 2011 and now again in 2015, officials are cautioning against using test scores to compare student achievement from year-to-year.

“The 2015 assessment should not and cannot be compared to the 2014 and 2013 assessment,” Rivera said. “It’s apples and oranges. Schools are still working on aligning curriculum to standards. They’re still catching up to teaching what we’re assessing.”

Each year students and teachers are told to hit a moving target, which was the reason also cited for caution four years ago.

While Rivera laments the issue and his inability to change anything soon within the government bureaucracy, parents are not thus encumbered.

All you have to do to save your child from being part of this outdated and destructive system is opt out.

But don’t stop there. Talk to other parents. Talk to classroom teachers. Organize informational get-togethers. Go to the PTA and school board meetings. Get others to join you.

And if the government threatens to withhold funding, lawyers are waiting in the wings to start the class action suits. Withholding taxpayer money expressly put aside to educate children because those same taxpayers disagree with government education policy!? Just try us!

Governments are tools but we hold the handles. If enough of us act this year, there will be no testing next year. Functionaries can threaten and foam at the mouth, but we are their collective boss. If they won’t do what we want them to do, we have the power to boot them out.

A multi-billion dollar industry has sprung up around high stakes standardized testing. Lobbying dollars flow from their profit margins into the pockets of our politicians. But we are more powerful.

Because you can’t serve your corporate masters if you are voted out of office.