Sometimes the truth is not enough.

Especially if you misunderstand its meaning.

That seems to be the main problem with a growth mindset.

It’s one of the trendiest concepts in education today, and – though it’s based on an authentic insight into how kids learn – it’s been shackled and monetized into an excuse to support a sterile status quo.

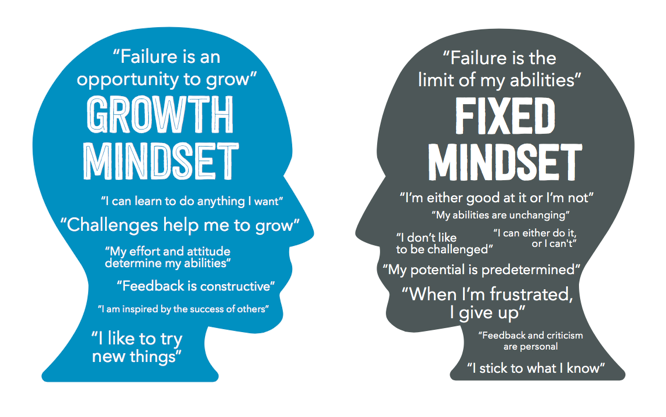

The basic idea goes like this: academic ability isn’t something students have or do not have. It’s a skill that gets better depending on how hard they work at it.

And up to that point, it’s correct and valuable.

But when we try to take that insight and weave it into current education policies, it becomes a shadow of itself.

As a middle school language arts teacher, I’m confronted with this most often in the context of standardized test scores.

I am constantly being told not to pay attention to the scores. Instead, I’m told to pay attention to growth – how much this year’s scores have improved from last year’s scores. And the best way to do this, I’m told, is by paradoxically examining the scores in the most minute detail and using them to drive all instruction in the classroom.

To me that seems to misunderstand the essential psychological truth behind a growth mindset.

Instead of focusing on the individuality of real human students, we’re zeroing in on the relics of a fixed mindset – test scores – and relegating the growth mindset to happy talk and platitudes.

B leads to A, and if we really want A, we just need to emphasize B.

To be clear, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the idea that learning is a skill that can be strengthened with hard work. I do, however, take issue with how that observation has been used to support the status quo of test-and-punish and strategic disinvestment in public schools. I take issue with the idea that growth is the ONLY factor in student learning and how we are ignoring the multitudinous ways the human mind works and what that means for education.

In short, I think making the growth mindset a magic bullet has ended up shooting us in the foot.

Here are six problems I have with the growth mindset model:

1) It Has Not Been Proven to Make an Appreciable Difference in Student Academic Achievement.

How exactly do you use growth to drive achievement?

You make the concept of growth explicit by teaching it. You actively teach kids this idea that anyone can learn with hard work, and the theory goes that they’ll achieve more.

Does it actually work?

The results have been pretty inconclusive.

It’s been tested numerous times in various ways – some showing success, some showing nothing or even that it hurts learning.

The best success has come from Carol Dweck, a Stanford education professor who’s made a name for herself promoting the growth mindset model in books and TED talks.

Just this month, she co-authored the largest nationwide study concluding that a growth mindset can improve student results.

About 12,500 ninth grade students from 65 public and private schools were given an online training in the concept during the 2015-16 school year.

The study published in the journal Nature concluded that on average lower-achieving students who took the training earned statistically significant higher grades than those who did not.

However, results were “muted” when students were less encouraged to seek challenges – such as when they had fewer resources and support.

Despite this success, Dweck’s peers haven’t been able to reproduce her results.

A large-scale study of 36 schools in the United Kingdom published in July by the Education Endowment Foundation concluded that the impact on students directly receiving this kind of training did not have statistical significance. And when teachers were given the training, there were no gains at all.

In a 2017 study, researchers gave the training to university applicants in the Czech Republic and then compared their results on a scholastic aptitude test. They found that applicants who got the training did slightly worse than those who hadn’t received it at all.

In 2018, two meta-analyses conducted in the US found that claims for the growth mindset may have been overstated, and that there was “little to no effect of mindset interventions on academic achievement for typical students.”

A 2012 review looking at students attitudes toward education in the UK found “no clear evidence of association or sequence between pupils’ attitudes in general and educational outcomes, although there were several studies attempting to provide explanations for the link (if it exists)”.

In short, there is little evidence that any current approaches to turning the growth mindset into a series of practices that increase learning at scale has succeeded.

2) It Doesn’t Fit with Current Education Policies

We live in a fixed mindset world.

That’s how we define academic achievement – test scores, grades, projects, etc.

We tabulate data, compile numbers and information and pretend that draws an accurate picture of students.

But the concept that student achievement isn’t one of these things – is, in fact, something changeable with enough effort – runs counter to everything else in this world view.

If data points don’t tell us something essential about students but only their effort, connecting them with high stakes is incredibly unfair.

Moreover, it’s incoherent.

How can you convince a student that test scores, for example, don’t tell us something essential about her when we put so much emphasis on them?

It’s almost impossible for students in today’s schools to keep a belief in a growth mindset when test scores and our attitude toward them confirm their belief in a fixed mindset.

In a world of constant summative testing, analysis and ranking of students, it is nearly impossible to believe in a growth mindset. It’s merely a platitude between the fixed academic targets we demand students hit.

This doesn’t exactly take anything away from the concept, but it shows that it cannot be implemented within our current educational framework.

If we really believed in it, we’d throw away the testing and data-centricity and focus on the students, themselves.

3) It Ignores Student Needs and Resources

When we try to force the growth mindset onto our test-obsessed world, we end up with something very much like grit.

After all, if the only factor students need to succeed is effort, then those who don’t succeed must be responsible for their own failures because they didn’t try hard enough.

And while this is true in some instances, it is not true in all of them.

Effort may be a necessary component of academic success but it is not in itself sufficient. There are other factors that need to be present, too, such as the presence of proper resources and support.

And most – if not all – of these factors are outside of students’ control. They have no say whether they are well fed, live in safe homes, have their emotional needs met. Nor have they any say whether they go to a well-resourced school with a wide curriculum, extracurricular activities, school nurses, tutors, mentors, psychologists and a host of other services.

Putting everything on growth is extremely cruel to students – much like the phenomenon of grit.

Education policy should help raise up struggling students, not continue to support their marginalization through poverty, racism and/or socioeconomic disadvantages.

4) It Can Make Kids Feel Disrespected and Disparaged

No child wants to be remediated.

It makes them feel small, inadequate and broken. And if they’re already feeling that way, it reinforces that helplessness instead of helping.

Context is everything. Well-meaning educators may gather all the students with low test scores in one place to tell them the good news about how they can finally achieve if they put in enough effort. But students may recognize this for what it is and instinctively turn away.

The best way to teach someone is often not to lecture, not to even let on that you’re teaching at all.

David Yeager and Gregory Walton at Stanford claimed in 2011:

“…if adolescents perceive a teacher’s reinforcement of a psychological idea as conveying that they are seen as in need of help, teacher training or an extended workshop could undo the effects of the intervention, not increase its benefits.”

Teachers cannot set themselves up as saviors because that reinforces the idea that students are broken and thus need saved.

I don’t think this is an insurmountable goal, but many growth mindset interventions are planned and conceived by non-teachers. As such, they often walk right into this trap.

5) It is Not Suitable For All Kids

Everyone’s minds don’t work alike.

When you tell some kids that anyone can achieve with enough hard work, it makes them discouraged because they thought that their academic successes marked them as special.

According to a 2017 study published by the American Psychological Association, growth mindset training can backfire especially with high achieving students for exactly this reason.

Hard work just isn’t enough for some students. Their self-esteem relies on the idea that they are good at school because of fixed qualities about themselves.

When we take that belief away, we can damage their self esteem and thus their motivation to do well in school.

The point isn’t that a growth mindset is wrong, but that as an intervention it is not appropriate for all students. In fact, perhaps we shouldn’t be using it as an intervention at all.

6) It Should Not be a Student Intervention. It Should Be a Pedagogical Underpinning for Educators

We’ve got this growth mindset thing all wrong.

It’s not a tool to help students learn. It’s a tool for teachers to better understand their students and thus better help them learn. It’s a tool for administrators, parents and policymakers to better understand what grades and test scores mean.

If you want to teach a student any skill, let’s call it X, you shouldn’t begin by telling them that anyone can learn it with enough effort.

Just teach X. And when you succeed, that will become all the motivation students need to learn the next thing.

Education is an incremental process. Success breeds success just as failure breeds failure.

As every teacher knows, you start small, scaffold your lessons from point A to B to C and make whatever changes you need along the way.

If we really want to help students in this process, we can start by ridding ourselves of the fixed mindset that current education policy is rooted in.

Growth mindset is a psychological observation about how human minds work. It’s not pedagogy. It’s empiricism.

We can use it to help design policy, lessons and assessment. But it has limited value – if any – being taught directly to students.

The growth mindset model has value, but not in the way it has typically been used in our school system.

Instead of providing justification for equitable resources and tearing down the testocracy, it’s been used to gaslight educators into obeying the party line.

It is not a magic cure all, but one factor among many that provides insight into learning.

If we can disentangle it from the profit-driven mire of corporate education, perhaps it can help us achieve an authentic pedagogy that treats every student as an individual and not an economic incentive for billionaires to pocket more tax money.

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!

Reblogged this on David R. Taylor-Thoughts on Education.

LikeLike

As much as I support making use of new research of how our brains work to facilitate learning, I look distastefully at how it will be rammed down our throats, how we’ll be expected to follow the dictates of those who’ll tell us how we’re resisting change if we don’t want to embrace their change, how our professional development will be delivered by someone with a book and/or program(and don’t forget the t-shirts) to sell, how it will only be a matter of time until the next new flashy thing will take its place. I’ve been in education now since the mid-70’s and have seen ideas recycled with new names and how each time we’re told how it’s the best and only way to teach. When whole language was king, I even had a principal tell us she’d better not catch us teaching how to diagram sentences. Since then, there have been a succession of administrators buying McLeader kits to buff up their resumes. I’m so tired of people who left teaching after a handful of years getting paid more than me to tell me how to teach. For crying out loud, give teachers some breathing room.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I hear you, Tom. There’s nothing wrong with new research but it should be driven by educators and not entrepreneurs looking to make a buck. Unfortunately that’s what’s become of our profession – it’s become a stepping stone to a higher income for influencers instead of about student outcomes. Hey, brother, can you spare some autonomy?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Growth Mindset “teaching” in Algebra I (public school) was the last straw for us. We were already tired of Common Core, really bad ed tech via really old 1:1 devices and the growth mindset pushed us over the edge with child #2. Child #2 now attends private HS that we pay for so that we can get away from all the test prep and tests. It’s been a hell of a summer in our house. Child #2 is to take Alg II as a sophomore this year and we knew that he would need some Alg I review. Little did we know that he learned very little of anything in Alg I….we have had to start at the very beginning of Alg I and teach the basic skills. Maybe if more time would have been spent teaching math instead of teaching Growth Mindset (which I raised a stink and my child got excluded from the “assignments”), we wouldn’t be living this hell. Also, 3 other families that moved their children out of public school are having the same problems.

LikeLike

Lisa, thanks for commenting. As a concept, growth mindset isn’t just a public school phenomenon. It’s everywhere – the same with standardized testing. I just wish more school boards would stand up for the children they’re supposed to be protecting. The entire profession is rife with profiteers trying to turn schools into money-making exercises without providing basic services to students. The way I see it, the answer to that isn’t more privatization, it’s less.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of the reasons more school boards don’t resist all this is that ambitious administrators have their ears most of the time. And why should they not listen to them? They’re being paid to be the experts. For every disgruntled parent or teacher association representative who speaks out, there’s a slick rebuttal (no doubt carefully composed and coached to adm. from the entrepreneurs). I have about five years left. My association isn’t interested in this battle, they can’t even get us a raise. Maybe when I retire, I can show up at more board meetings and raise a little hell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

THANK YOU!! I have always hated this “growth mindset” stuff, but I couldn’t really put into words why it bothered me so much. You have put words to my uneasiness. I truly appreciate it, because I can now verbalize it to others.

You rock!

LikeLike

I know what you mean. It took me a while to be able to verbalize it, too. Thanks for commenting.

LikeLike

This is such a relevant and important topic! This Growth Mindset as any other ideas like the “Leader in Me” pitched by the corporate reformers, seems nothing more than an attempt to create the next fashion in public education. As it has happened with neoliberal proposals, Growth MIndset was preceded by a solid advertisement that introduced it as a new and necessary tool to finally revolutionize education. Not surprisingly, it appeals to the neoliberal crowd. The elements of Growth Mindset embraces and validates the individualism, the competitiveness, and the choice that free-market ideology values so much. Could it be a useful and well intended idea? Perhaps. But, in reality has become another business that profits from public schools’ funds. And in the meantime, it will keep educators busy enough not to pay attention to the unraveling plan that is privatizing our public school system. Teachers will keep playing this perversely rigged game, thinking that this time there is a chance to win.

It never ceases to amaze me how after decades of enriching themselves with tax-payers money through consulting schemes, corporate reformers manage to sell yet more new business ideas that despite not being warranted or validated by evidence, become popular and very profitable at least for a few years. Consultants came and went in my district. Some of them left with half a million dollars after only three years of trying to make their program work for the district, but not succeeding mainly because faulty implementation. At least it is what we were told. I wonder how much money the company behind Growth MIndset has made, and how much more it will make before something else come along.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sergio. I love how you connect this with economic forces. It’s an important point often ignored.

LikeLike

[…] Source: Six Problems with a Growth Mindset in Education | gadflyonthewallblog […]

LikeLike

[…] there is not always a natural progression from Point A to B to C. Sometimes A jumps directly to C. Sometimes B leads directly to A. Sometimes A leads to […]

LikeLike

[…] Either way, standardized assessments are supposed to be based on what students have learned. But the problem is that not all learning is equal. […]

LikeLike

[…] Growth!? […]

LikeLike

[…] Six Problems with a Growth Mindset in Education | gadflyonthewallblog […]

LikeLike

[…] 9) Six Problems with a Growth Mindset in Education […]

LikeLike

[…] when you’re dealing with something as complex as the minds of children, this approach is destined for […]

LikeLike

[…] when you’re dealing with something as complex as the minds of children, this approach is destined for […]

LikeLike

[…] when you’re dealing with something as complex as the minds of children, this approach is destined for […]

LikeLike

[…] is not quantifiable in the way they pretend it is and teaching is not the hard science they want it to […]

LikeLike

This was great. Not sure if you’ve heard of Alfie Kohn but he has a great book titled “No Contest: The Case Against Competition,” where he cites dozens of studies that debunks conventional wisdom about the ethos of competing in education, the workplace, and in larger society.

It’s a really good read and I think it can help build your argument even more.

LikeLike

I love Alfie Kohn!

LikeLike

[…] Both types of assessment are supposed to measure what students have learned. But not all learning is equal. […]

LikeLike