When I was a child, I couldn’t spell the word “principal.”

I kept getting confused with its homonym “principle.”

I remember Mr. Vay, the friendly head of our middle school, set me straight. He said, “You want to end the word with P-A-L because I’m not just your principal, I’m your pal!”

And somehow that corny little mnemonic device did the trick.

Today’s principals have come a long way since Mr. Vay.

Many of them have little interest in becoming anyone’s pal. They’re too obsessed with standardized test scores.

I’m serious.

They’re not concerned with student culture, creativity, citizenship, empathy, health, justice – they only care about ways to maximize that little number the state wants to transform our children into.

And there’s a reason for that. It’s how the school system is designed to operate.

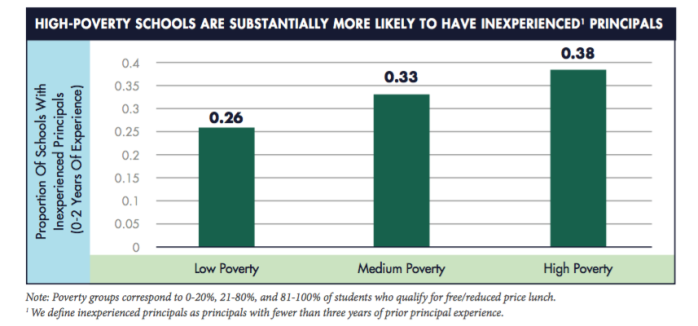

A new research brief from the Tennessee Education Research Alliance concluded that the lowest rated principals generally work at schools with the most economically disadvantaged students.

Now the first question I had when reading this report was “How do they measure effectiveness?” After all, if they rate principals primarily on student test scores, then obviously those working at the poorest schools will be least effective. Poor kids earn low test scores. That’s all the scores consistently show – the relative wealth of students’ parents. If you define an ineffective principal as one who works in a building with low scoring students, it would be no shock that those principals worked in the poorest schools.

However, researchers didn’t fall entirely into this trap. According to the working paper:

“We measure principal quality in two ways: years of experience in the principal position and rubric-based ratings of effective principal practice taken from the state’s evaluation system.”

In Tennessee this means evaluating principals partially on student test scores at their buildings – 35%, in fact – higher than the 20% of classroom teachers’ evaluations. However, the remaining pieces of principals’ effectiveness are determined by an observation from a more senior administrator (50%) and an agreed upon score by the principal and district (15%).

Since researchers are relying at least in part on the state’s evaluation system, they’re including student test scores in their own metric of whether principals are effective or not. However, since they add experience, they’ve actually created a more authentic and equitable measure than the one used by the state.

It just goes to show how standardized testing affects nearly every aspect of the public education system.

The testing industrial complex is like a black hole. Not only does it suck up funding that is desperately needed elsewhere without providing anything of real value in return, its enormous gravity subverts and distorts everything around it.

It’s no wonder then that so many principals at high poverty schools are motivated primarily by test scores, test prep, and test readiness. After all, it makes up a third of their own evaluations.

They’ve been dropped into difficult situations and made to feel that they were responsible for numerous factors beyond their control. They didn’t create the problem. They didn’t disadvantage these students, but they feel the need to prove to their bosses that they’re making positive change.

But how do you easily prove you’ve bettered the lives of students?

Once again, standardized test scores – a faux objective measurement of success.

Too many principals buy into the idea that if they can just make a difference on this one metric, it will demonstrate that they’re effective and thus deserve to be promoted out of the high poverty schools and into the well-resourced havens.

Yet it’s a game that few principals are able to win. Even those who do distinguish themselves in this way end up doing little more for their students than setting up a façade to hide the underlying problems of poverty and disinvestment.

Most principals at these schools wind up endlessly chasing their tails while ignoring opportunities for real positive change. Thus they end up renewing the self-fulfilling prophesy of failure.

Researchers noticed the pattern of low performing principals at high poverty schools after examining a decade’s worth of data and found it to hold true in urban, rural and suburban areas. And even though it is based on Tennessee data, the results hold true pretty consistently nationwide, researchers say.

Interestingly enough, the correlation doesn’t hold for teachers.

Jason Grissom, an associate professor at Vanderbilt University and the faculty director of the Research Alliance, says that the problem stems from issues related specifically to principals.

For instance, districts are hiring lower-rated principals for high poverty schools while saving their more effective leaders for buildings with greater wealth and resources.

As a result, turnover rates for principals at these schools are much higher than those for classroom educators. Think about what that means – schools serving disadvantaged students are more likely to have new principal after new principal. These are leaders with little experience who never stick around long enough to learn from their mistakes.

And since these principals rarely have had the chance to learn on the job as assistant principals, they’re more likely to be flying by the seat of their pants when installed at the head of a school without first receiving the proper training and mentorship that principals at more privileged buildings routinely have.

As such, it’s easy for inexperienced principles to fall into the testing trap. They buy into the easy answers of the industry but haven’t been around long enough to learn that the solution they’re being sold is pure snake oil.

This has such a large effect because of how important principals are. Though they rarely teach their own classes, they have a huge impact on students. Out-of-school factors are ultimately more important, but in the school building, itself, only teachers are more vital.

This is because principals set the tone. They either create the environment where learning can flourish or smother it before the spark of curiosity can ignite. Not only that, but they create the work environment that draws and keeps the best teachers or sends them running for the hills.

The solution isn’t complicated, says Grissom. Districts need to work to place and keep effective and experienced principals in the most disadvantaged schools. This includes higher salaries and cash bonuses to entice the best leaders to those buildings. It also involves providing equitable resources for disadvantaged schools so that principals have the tools needed to make authentic positive change.

I would add that we also need to design fair evaluation systems for both principals and teachers that aren’t based on student test scores. We need to stop contracting out our assessments to corporations and trust our systems of government and schools to make equitable judgments about the people in their employ.

Ultimately, what’s required is a change in attitude.

Too many principals look at high poverty schools as a stepping stone to working at a school with endless resources and a different class of social issues. Instead, the goal of every excellent school leader should be to end their career working where they are needed most.

Such professionalism and experience would loosen the stranglehold of test-and-punish and allow our schools not to simply recreate the inequalities already present in our society. It would enable them to heal the divide.

As John Dewey wrote in 1916:

“Were all instructors to realize that the quality of mental process, not the production of correct answers, is the measure of educative growth, something hardly less than a revolution in teaching would be worked.”

And that’s what’s needed – a revolution.

Still can’t get enough Gadfly? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!

[…] (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); This is only a snippet of a Education Article written by stevenmsinger Read Full Article […]

LikeLike

What is the new profile of school administration in the neoliberal model? When NCLB was enacted, a new paradigm of roles and responsibilities for all educators in public education was imposed. This free-market vision made structural changes that affected both teachers and principals alike. Undeniable, teachers have had to endure being demoted from professionals to practically technical labor, losing their civic role as stakeholders. But equally factual is that principals have been placed in this free-market limbo of middle management when results are demanded or else they are incompetent. In appearance, the responsibilities and the duties of principals remain the same as they were prior to the corporate reforms; in reality, the current version imposes an arbitrarily public scrutiny in a punitive system that evaluates unwarranted results of a set of scores. This brought a dramatic change of paradigm: Principals are no longer leaders in a community; they are managers of a business.

Imitating business management, schools principals were asked to see numbers and make decisions. And as expected from copying the business world, administrations were asked to accept that lacking the expected results will indicate their own inability for the job. In this toxic, arbitrarily, competitive environment, improving scores has become the only valid measure to indicate their success or failure as principals. Consequently, a significant part of administration has been devoted to learn from the business models how to be efficient using the available human resources –ideally, running meetings and make teachers do more and better. Thus, schools teachers are now having more meetings and committees than ever before, and guided by strict agendas that indicate roles and responsibilities to justify every minute spend.

Not surprisingly, the new public school administrator must show the qualities of a good sales person. For principals, new and experienced in this century, this neoliberal model of school administration that requires being visible and eloquent enough to promote and sell the new vision for the school has been the norm. Administrators have to be decisive and firm, demanding and confident, while delegating and making every teacher individually and in teams accountable under their new vision of running the business. In a nutshell, the neoliberal system asks principals to sets goals to increase scores from period to period, and demands results from a workforce that has embraced the new style of doing business.

Who is a good principal? Since socio-economic contexts do not matter in this neoliberal vision, principals are not expected to be leaders in the community anymore. Good principals are supposed to be effective employees –likable, hard-working, team players, go-getters– in a business that is supposed to deliver scores. After all, the general public has been instructed to use the published scores and evaluate schools, teachers, and principals as well. Instinctively for principals, thinking about the unwarranted scores of their own and of other neighboring schools, in order to see how to increase them is their job’s premier reason and goal –their resume will show their achievements. The cold hard numbers guide and dictate principals’ decisions. And understandably, the perception of scoring poorly or low in a punitive system is both demoralizing for the workforce.

In order to help every school, it is imperative to see the disastrous results –social and economic—that the corporate reforms have both neglected to see, and produced. This business model has not delivered any solution, and it has indeed made it more complicated to improve public education. It is time to acknowledge that schools in underprivileged communities are unfairly competing with every other school in their community, and unavoidably compared with other similar ones.

It is important to recognize as well the fallacy that the free-market environment uses as a premise for improvement — schools are supposed to increase scores if good leadership is brought. This way of thinking in the business model that assumes that a new and improved product will certainly do the job, does not apply in public education. Scores are not supposed to be the whole story of each school or district, it is just a measure. If we are serious about improving public education for all, we have to reject the neoliberal ideology and loot at, and attend to the roots of the problems.

Indeed, there are many good, capable, and caring principals. What we need is to nurture them and let them become the leaders and models they can and should be. Condemning to be just the managers of stores is simply a disservice to their talent and experience.

Who wins, who loses, who cares?

In solidarity,

Sergio Flores

LikeLiked by 1 person

Damn, Sergio! There is so much truth in what you wrote. Mic drop.

LikeLike

[…] Source: The Trouble with Test-Obsessed Principals | gadflyonthewallblog […]

LikeLike

[…] pats himself on the back for raising principals’ salaries and recruiting only people who think and believe just like him. Then he didn’t have to watch over them so closely and they were even promoted to higher […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on David R. Taylor-Thoughts on Education.

LikeLike

[…] Numbers, charts and graphs were used to mesmerize people into going along with policies that were never meant to help children learn, but instead to gain power for certain policymakers while taking it away from others. […]

LikeLike

[…] Now teachers who receive Unsatisfactory evaluations – even if that only means they need improvement – are the first to go. It allows administrators to stack the deck against teachers they don’t like, teachers at the top of the pay scale or who advocate for policies different than those favored by the bosses. […]

LikeLike

[…] We’ve become so obsessed with these scores – a set of discrete numbers – that we’ve lost sight of what they always were supposed to be about in the first place – learning. […]

LikeLike

[…] We’ve become so obsessed with these scores – a set of discrete numbers – that we’ve lost sight of what they always were supposed to be about in the first place – learning. […]

LikeLike

[…] We’ve become so obsessed with these scores – a set of discrete numbers – that we’ve lost sight of what they always […]

LikeLike

[…] The principal can’t educate classes from his desk in the administrative office. The school board director can’t do it from his seat in council chambers. Lawmakers can’t do it from Washington, DC, or the state capital. Only the teacher can do it from her place in the classroom, itself. […]

LikeLike

[…] But I choked down my response and waited for someone to tell him what he wanted to hear. […]

LikeLike

[…] Test-obsessed policy makers will tell educators to manage everything with a clipboard and a spreadsheet – for example, to increase the percentage of positive interactions vs negative ones in a given class period. But such a data-centric mindset dehumanizes both student and teacher. […]

LikeLike

[…] Increasingly schools enroll students based primarily on their test scores. […]

LikeLike

[…] And any administrator or school director who can’t see that is incredibly naive. […]

LikeLike

[…] These folks pretend that learning is all about numbers – test scores, specifically. […]

LikeLike

[…] kinds of principals – and we know who you are – have checklists of every teacher in the building and simply mark off your name to designate […]

LikeLike

[…] to fill out lesson plans that administrators don’t have time to read and (frankly) probably don’t have the training or experience to fully comprehend is top down managerial madness. […]

LikeLike

[…] get to interact with principals as they’re told which additional classes they have to cover in their planning periods and which […]

LikeLike

[…] However, you’d need a classroom teacher to explain that to you. And these are more business types. Administrators and number crunchers who may have stood in front of a classroom a long time ago but escaped at the first opportunity. […]

LikeLike

[…] could be an administrator who made another stupid initiative that makes him/her look good while increasing your work load but does nothing to help the […]

LikeLike

[…] certain administrators just love these pre-tests. They love looking at spreadsheets of student data and comparing one grading period to another. […]

LikeLike

[…] certain administrators just love these pre-tests. They love looking at spreadsheets of student data and comparing one grading period to another. […]

LikeLike

[…] year at my Western Pennsylvania district, administration decided to use this computer-based standardized assessment as a pre-test or practice … before the state mandated Pennsylvania System of School Assessment […]

LikeLike

[…] has huge implications for the quality of education being provided at our schools. Since most administrators have drunk deep of the testing Kool-Aid, they now force teachers to educate in just this manner – to use test scores to drive […]

LikeLike

[…] Today’s principal is a frightening thing. After decades of educational malpractice at colleges and universities in creating new school administrators, principals no longer understand what their job truly is. […]

LikeLike

[…] my own admittedly limited experience, the most test obsessed teachers and administrators I have ever know have been people of color – almost as if they were trying to make a point […]

LikeLike