Hard work should be rewarded.

If you earn an A in a given class, you should get an A on your report card.

And this is true no matter how many of your classmates work just as hard as you do.

If everyone in class gives it their best shot, they should all get A’s. It is not the teacher’s job to split hairs and sort kids into arbitrary categories in order to preserve a monetary myth about grades’ value based on a model of scarcity.

Those who demand otherwise are under the spell of one of the oldest myths in academia – grade inflation.

It goes like this: You can’t give all your students excellent marks! That would devalue what it means to get an A!

To which I reply: Bullshit.

Almost every plane that leaves an airport lands safely. Does that devalue what it means to travel? When you arrive at your destination, are you upset that everyone else has arrived safely or would you feel better if some of the planes crashed?

According to the American Journal of Public Health, 93% of New York City restaurants earn an “A” from the health department. Does that shake your faith in the food service industry? Would you feel better if more restaurants were unsanitary? Would your food digest more efficiently if there were more people going home with stomach pain and food poisoning?

Of course not! In fact, these stats actually reassure us about both industries. We’re glad air travel and eating out is so safe. Why would we feel any different about academia?

The idea of grade inflation is a simple imposition of the concept of economic value onto learning. It has no meaning in the field of academics, psychology or ethics. It is just some fools who worship money imaging that the whole world works the same way – and if it doesn’t, it should.

It’s nothing new.

Conservatives have been whining about grade inflation for at least a century. It’s not that the quality of teachers has declined and they’re letting all their students pass without doing the work. It’s that certain types of curmudgeons want to justify their own intelligence by denying others the same privilege.

It’s the “I’ve Got Mine” philosophy.

We see the same thing with Baby Boomers who grew up in the counter culture and pushed for progressive values in their youth. Once they got everything they wanted for themselves, they became conservatives in their old age and worked to deny the same things for subsequent generations.

It’s the very definition of Age scoffing at Youth – a pathology that goes back at least to Hesiod if not further. (Golden age of man, my foot!)

Moreover, there is no authentic way to prove grade inflation is actually happening. Grades are a subjective measure of student learning. They are human beings’ attempt to gauge an invisible mental process. At best they are frail approximations of a complex neural process that is not even bounded temporally or causally. If a student doesn’t know something now, they may come to know it later even without further academic stimulus. Moreover, isolating the stimulus that produced the learning is also nearly impossible.

The important thing is not grade inflation. It is ensuring that grades are given fairly.

If students work hard, they should be rewarded.

I am very upfront with my students about this. And doing so seems to have a positive and motivating effect on them.

This year, I had students who told me they had never read a book from cover-to-cover before my class. I’ve had students look at their report cards in shock saying they’ve never received such high marks in Language Arts before. And doing so makes them want to try all the harder next year to repeat the results.

They leave me excited about learning. They feel empowered and ready to give academics their all. Because the greatest lesson a teacher can instill is that the student is capable of learning.

Don’t get me wrong. I don’t just hand out these grades. Students have to earn them. They have to demonstrate that they have actually learned something.

Everyone rarely measures up to the challenge. But that’s not the point. Everyone COULD. There is nothing in my design that prohibits that outcome. I don’t start with the assumption that I’ll only have 3 A’s, 4 B’s, 10 C’s, etc.

In fact, it is THAT scarcity model that dumbs down academics. If I grade on a curve like that, I have to give out a certain number of high marks regardless of achievement. I’m committed to giving out those 3 A’s regardless of whether that trio of students deserve it or not. However, in my abundance model, I give exactly the number of A’s that are deserved. If that’s zero, no one gets an A. If that’s everyone, then everyone gets an A. It all depends on what students actually deserve, not some preconceived notion about how the world works.

To do this, I give very few tests. I just don’t find them to be very helpful assessments.

A test is a snapshot of student learning. It has its place, but the information it gives you is very limited.

Most of my grades are based on projects, homework, essays, class discussion, creative writing, journaling, poetry, etc. Give me a string of data points from which I can extrapolate a fair grade – not just one high stakes data point.

This may work to some degree because of the subject I teach. Language arts is an exceptionally subjective subject, after all. It may be more challenging to do this in math or science. However, it is certainly attainable because it is not really that hard to determine whether students have given you their best work.

Good teaching practices lend themselves to good assessment.

You get to know your students. You watch them work. You help them when they struggle. By the time they hand in their final product, you barely need to read it. You know exactly what it says because you were there for its construction.

For me, this doesn’t mean I have no students who fail. Almost every year I have a few who don’t achieve. This is usually because of attendance issues, lack of sleep, lack of nutrition, home issues or simple laziness.

I only have control over what happens in the classroom, after all. I can call home and try to work with parents, but if those parents are – themselves – absent, unavailable or unwilling to work with me, there’s little I can do.

And before you start on about standardized testing and the utopia of “objectivity” it can bring, let me tell you about one such student I had who was not even trying in my class.

He never turned in homework, never tried his best on assignments, rarely attended and sleepwalked through the year. However, he knew his only chance was the state mandated reading test – so for three days he was present and awake. The resulting test score was the only reason he moved on to the next grade.

Was he smart? Yes. Did he deserve to go on to the next grade not having learned the important lessons of his classmates? No. But your so-called “objective” measure valued three days of effort over 180.

The problem is that we are in love with certain academic myths.

MYTH 1: Grading must be objective.

WRONG! Grading will never be objective because it is done by subjective humans. These standardized tests you’re so in love with are deeply biased on economic and racial lines. Whether you pass or fail is determined by a cut score and a grading curve that changes from year-to-year making them essentially useless for comparisons and as valid assessments. They’re just a tool for big business to make money off the academic process.

MYTH 2: Learning is Economics.

WRONG! Grades are not money. They don’t function in any way like currency or capital. They aren’t something to be bought and sold. They are an approximate indication of academic success. Treating them as a commodity only degrades their value and the value of students and learning, itself.

Treating grades economically actually represses the desire to learn, dispels curiosity and eliminates the intrinsic value of education.

So go ahead – inflate the “value” of your grades.

Give A’s to every student who deserves it.

That’s how you promote learning and fairly assess it.

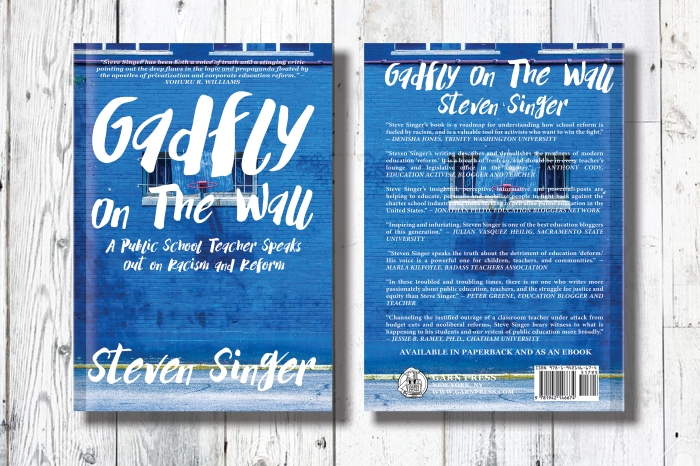

Like this post? I’ve written a book, “Gadfly on the Wall: A Public School Teacher Speaks Out on Racism and Reform,” now available from Garn Press. Ten percent of the proceeds go to the Badass Teachers Association. Check it out!

WANT A SIGNED COPY?

Click here to order one directly from me to your door!

Hmmm… You say, “A test is a snapshot of student learning. It has its place, but the information it gives you is very limited.” What kind of snapshot is it, and what’s its real importance if it’s so limited and yet given such inordinate weight? Why not just abandon the whole system, and use the methods that give a true, accurate, and comprehensive picture of what is learned? That would be: a meaningful conversation about learning. If grades were abandoned entirely, and the system were geared to true and deep conversations, both students and teachers would be so much better off. I know it can be done: I went to Westland School in LA in the 1950’s, where no grades were ever given and passing from group to group (they deliberately abandoned the term “grade” for the students who formed a community each year in each classroom) was decided by a conference among the teacher, the student, and the student’s family. It worked then, and it still works today, almost 70 years later… Westland is going strong!

LikeLike

Perhaps you’re right. I find the suggestion fascinating though I’m not quite sure it would work in all cases. One needn’t go to this extreme. You can still have grades and not give in to grade inflation. But it could be that – as you suggest – we could go even further and dispense with grades altogether. I’ll certainly be reading more on this subject.

LikeLike

Excellent column – I agree so much about the “fairness” of giving a child what they deserve, regardless of what the “bell curve” or any other measurement may suggest as being “fair” or “true.”

I’m giving you an A- (oops! why the “minus?”)

“They leave me excited about learning. They feel empowered and ready to give academics THERE all.”

(you’ll find it about 1/3 of the way down from the top)

(probably just excited about creating such a great column!!!)

LikeLike

Oh, my!

I corrected something in the original post and noted it in my recent reply – in a nice way (so I thought).

I see that the second part of my first reply is missing – and the “typo” has been corrected.

Does that mean you don’t want your parents to see your grade?

LikeLike

Sorry, Blassball. I thought you meant that part as a private message. Didn’t mean to insult you. I appreciate the catch and the spirit in which it was given.

LikeLike

I am curious about how you weight a) trying hard b) doing what the teacher tells you to do and c) achievement of outcome in your grades. I ask my students to do many things, but the grades I give are largely determined by exams results. Those are the assignments that I am reasonably certain are the sole product of the student.

You said that a student went on to the next grade based on an exam score and you felt that illegitimate. Would it be legitimate to allow an illiterate student to go on to the next grade?

LikeLike

Teaching economist, you are a true believer in exams, aren’t you? Let me ask you a few questions: Do you create the exams used in your course or are they created by a private corporation that profits off of student failure? Have your exams ever been proven to demonstrate or promote student learning? If someone passed your final exam without appearing in your class, purchasing the books or doing any classwork, do you think that would demonstrate mastery of the subject or that they may have cheated?

As to illiterate students passing my course, that has never happened. Nor have I ever had an illiterate student enter my 7th or 8th grade classes. However, most of my students enter my class reading below grade level – often many years below grade level. They leave after making tremendous progress but not all make it up to grade level in only one year and without the benefit of a reading specialist. Research tells us that failing such students would not help them achieve. It would only prove to them that learning was unattainable. Much better to give a student who is progressing the chance to progress further.

LikeLike

Steven,

I have spent 30 years writing my exams, so I have refined them a bit over the years. My final exam is only 20% of the grade, so if a student had skipped the other 4 exams, it is unlikely that they will pass my class.

What of the students in your class that try very hard but do not make tremendous progress? Do you simply pass them along to the next grade?

I again ask my original question: what is the mix of a) effort, b) obsequiousness, and c) achievement that goes into determining your grades? My worry is that I have given too much weight to obsequiousness, so I will be computing grades two ways in the future: one based on the 5 exams i give during the semester, and the other including the 60 other pieces of work that I ask students to do during the semester. Do you think that is too little weight for obsequiousness?

LikeLike

If you write your own exams, then I’m sure you share my distaste for standardized assessments written by for-profit companies that reward good test takers but not necessarily comprehension of the material. You also must share my outrage over my student who did none of the classwork but passed due solely to one standardized score.

You may not believe this, but when it comes to effort, I have never had a student who tried hard and didn’t make significant progress. Of course this is after taking into consideration disabilities, IEPs, ELLs, etc. In general, if you work hard you can accomplish anything. Or at very least you can make progress.

As to weight, I’m not sure I can accurately divide grades based on your criteria. When a student does well on your exams, is that because they learned the material, they tried hard or they listened to your instructions? Learning is complex. Grades are simple. They cannot capture all the variables.

I know you’re worried about obsequiousness, and with good reason. Rule followers tend to get better grades than independent thinkers. However, if you foster a classroom culture that rewards independent thought over obsequiousness, you can minimize this to some extent. But college courses are run much differently than grade school ones. We rarely lecture. Our students learn by doing – often in class with the teacher working as a facilitator. This may not work for you. But maybe if you can incorporate more of this in your lessons, you’ll minimize the obsequiousness.

LikeLike

[…] who just aren’t trying hard enough might be incentivized by threats. But even then it transforms learning into a means to an end. Once you do that, you destroy their natural curiosity. Learning will never again be an end in […]

LikeLike

[…] I tell my students explicitly that anyone who puts in their best effort will pass my class – proba…. And that’s exactly what happens. […]

LikeLike

[…] –Check and double check to make sure you have created a fair and accurate assessment before giving it to students to evaluate their […]

LikeLike

[…] The test makers generally come from the same socioeconomic group as the highest test takers do. So it’s no wonder that children from that group tend to think in similar ways to adults in that group. […]

LikeLike

[…] this student cares about getting a good grade, to be judged proficient and to move on to the next task in a series of Herculean labors. But does […]

LikeLike

[…] We’ve become so obsessed with these scores – a set of discrete numbers – that we’ve lost sight of what they always were supposed to be about in the first place – learning. […]

LikeLike

[…] We’ve become so obsessed with these scores – a set of discrete numbers – that we’ve lost sight of what they always were supposed to be about in the first place – learning. […]

LikeLike

[…] these scores – a set of discrete numbers – that we’ve lost sight of what they always were supposed to be about in the first place – learning. […]

LikeLike

[…] class, students can speak with teachers about grades to get a better sense of how and why they earned the m…. They can then use this explanation to guide them in the future thus tailoring the classroom […]

LikeLike

[…] – and one that media doom-mongers love to repeat – is that districts like mine routinely inflate mediocre achievement so that bad students look like good ones. […]

LikeLike

[…] already double points for the last grading period. Doing that and having such a hefty final project sends the message to kids that they can’t slack off now. The work they do in the closing days of […]

LikeLike

[…] one level, students are assessed by their teachers. They grade assignments, give tests, etc. However, this is similar to the game, itself. When you […]

LikeLike

[…] one level, students are assessed by their teachers. They grade assignments, give tests, etc. However, this is similar to the game, itself. When you […]

LikeLike